(Continued from here.)

I once had a problem with my daughter Eva. She was almost eleven years old and loved to read. That wasn’t the problem. The problem was that for homework Eva’s teacher wanted her to write in a journal about what she read. It’s not that the teacher wanted Eva to write anything sophisticated, just to talk about what she loved in this or that passage of a book of her choosing. She didn’t have to write a lot, a page or two a week would do. Fifteen minutes a day. But each day when I reminded her, she made this face, scrunched up her eyes and nose, and said, “I’m busy. I’ll do it later.” And then the night before it was due, simply: “I’m not doing it.” Eva was attending a so-called “open school” where one of the central beliefs is that a child ought to participate actively in her learning, select “home” activities that are fun and engaging. I reminded her of this:

“But Eva you picked this assignment together with your teacher. I mean, you chose this. And besides, you love to read.”

“Yeah,” her voice rose, “I love to read, Dad, read, not write about it.”

“But maybe it would be good to discover what you love about it, no?”

“That’s not how I read,” she countered, “I just read it, finish it and I’m done.”

“But,” I offered, “don’t you want to be able to talk with others about what you’ve read, to tell your friends about books you’ve liked, just to share the good feeling, and maybe even to get them interested enough to want to read it too?”

“I just wanna say that ‘this book is great, you should read it.” And with that, she stalked off into her room.

Of course, getting a child to do something they don’t want to do is not an unusual situation. At this very moment, parents all over the world are facing something similar and solving it, or not, according to their own resources, values, and the pressures of the moment. I might naturally have turned for advice to more experienced parents, or to the innumerable parenting manuals available today, or, even to works specializing on child development, psychology or education. But I didn’t consult any of these resources. Instead, I responded with my own resources: a combination of love for my child, my own experiences as a reader, and my ideas about reading drawn from years working as a literature professor.

That work as a professor included an experience that in some ways resembled Eva’s struggles. I was part of an interviewing team searching to hire a faculty member in Latino studies. The person we were interviewing was a rising star in the field and had finished a book manuscript on some writers she was characterizing as diasporic Puerto Ricans. Her very valid point was that if one saw them this way instead of as just Americans one would see something previously unseen in their writing. Among the authors she discussed was William Carlos Williams.

Now to be truthful I didn’t know a whole lot about her field, or about the other writers she worked on and I don’t in fact know very much about Williams. I’ve read a biography and some of his books, but I’ve never carried out a scholarly investigation of Williams’ writing. That’s probably why when I heard the name I got excited. One of my favorite poems of all time is Williams’ “The Red Wheelbarrow” and I was curious to know what she thought of it as an “expert.” I expected that she’d unfold for me some new intensely joyful corner of this poem. So after the other committee members, specialists in her field, talked with her about theory and culture and the canon of American studies, it was my turn.

I said, “This isn’t really an interview question. I just really love “The Red Wheelbarrow” and wonder what you have to say about it.”

She paused and replied, “I haven’t thought about it.”

I persisted, “Do you like it?”

She was enthusiastic: “Oh yes, of course! I love that poem!” And then, after a pause and with less enthusiasm, she concluded, “it just doesn’t fit with the rest of the stuff in the Williams chapter.”

I was disappointed, and though I kept it to myself, I felt as though she had failed or worse, actively committed some transgression. If she loved a text but couldn’t find room for it within her theoretical paradigm, there must be something wrong with her theoretical paradigm and something wrong with her, too, that she would sacrifice a beloved poem for the sake of methodological neatness (or worse, academic fashion). But as time passed, I realized she was not the problem. Nor do I think I was the problem.

I simply wanted to have a certain kind of conversation about a poem, but that conversation couldn’t really get off the ground within the circumstances in which I was trying to have it. By that I mean not only the setting of an academic job interview, but the conventions of academic training and of professional reward. The experience became an index pointing me back to my own feeling of the increasing intolerability of what had come to feel like a mutually exclusive set of imperatives. One must either read for fun or read for professional success; read for joy or read for work, read for love or read to think, in short, the very same set of oppositions that seemed to be governing my daughter’s impasse in her homework.

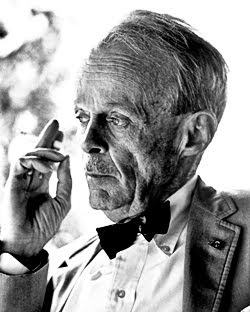

|

| John Dewey (1859-1952) |

Around the same time, I ran across a passage from John Dewey’s book, Art as Experience. I wasn’t looking for any solutions in Dewey, but rather just allowing myself to be led by my fascination with his clear and concrete way of talking about art. I emphasize that because it often happens with reading to live that encountering texts without pre- calculation often leads to surprisingly relevant insights. Dewey was an American philosopher, an heir to the so-called Pragmatist tradition expounded by William James earlier in the century. I had loved James’ style of writing and his informality, but had turned to Dewey because, in part, he wrote directly about art.

The particular passage that struck me was part of Dewey’s discussion of the ways in which art and our experience of it challenges certain assumptions that philosophers might make when looking at the world. In this case, Dewey was looking at theories of art as illusion, dream, escape, or play. Dewey objected to these theories not because art cannot be all of these things, but rather because art is so much more than all of these things. In fact, art, according to Dewey is the experience of the boundary dissolving between these things and their supposedly mutually exclusive opposites of reality, waking life, imprisonment, or work. Seeing it this way, in turn, led Dewey to question the much more fundamental philosophical dichotomy between subject and object, or self and world.

When we view art as an “escape” or a “release” from reality, Dewey believed, we implicitly suppose “freedom can be found only when personal activity is liberated from control by objective factors.” We implicitly take what Dewey called “experience” – the ceaseless exchange of matter and energy of a live creature growing in and with its surroundings – and we first freeze it in time and then split it into two opposed and mutually exclusive halves. On one side is the live creature, which we call a “subject” or “self,” together with its desires. On the other side, the surroundings, including other subjects, which we call “objects” or “others,” together with the limitations we perceive these surroundings impose on us. Therefore in viewing art as an escape from reality we implicitly pretend to isolate our “self” from everything that we perceive as “outside” of and oppressive to it. “Play” then becomes the name for what we can do when we suppose ourselves to be free of objective limitations. “Work,” by contrast, becomes the name for what we do the rest of the time, when we numbly or sullenly submit to those limitations – or attempt to manipulate them from a utilitarian distance -- and thereby protect our “self” through a detached intellectual posture. All the while, we forget that we made these distinctions and opposed them to each other.

But for Dewey, “the very existence of a work of art is evidence that there is no such opposition between the spontaneity of the self and objective order and law.” True, Dewey admitted, “the contrast between free and externally enforced activity is an empirical fact.” However, he added, “it is largely produced by social conditions and it is something to be eliminated as far as possible.” It is a sad mistake to see this social and historical condition as natural and immutable. And perhaps even sadder to see it and just let it be. After all, as Dewey points out, “children are not conscious of any opposition between play and work.”

Of course, here I remember thinking “Well he doesn’t know my kid.” But I see that it wasn’t until the structure of school, the importance of grades, and the assigning of homework entered her life that Eva started to experience the difference between learning as play and learning as work. She was, after all, nearly eleven and already much exposed to, this opposition between play and work, and also to my modeling of it. Dewey’s point is that there’s nothing natural or given or unchangeable about this and art can be a way to rub away at this stark opposition. It invites us to participate in and experience as integrated what have become for most of us two mutually exclusive ways of engaging a world of existence that we have divided into two mutually exclusive parts.

I’d like to recast this opposition between play and work into a slightly different vocabulary. The philosopher Neal Grossman devotes a chapter of his commentary on Spinoza’s Ethics to the latter’s theory of desire and emotion.

I want to draw your attention to a few pages in Grossman’s Healing the Mind because of their affinities with the problem at hand. Grossman emphasizes the critical role that the cultivation of the nonjudgmental awareness of affect plays in Spinoza’s Ethics. In emphasizing this role, Grossman pauses to describe what he calls “social schizophrenia” or “the split or incongruity between inner feelings and outer behavior.” His argument is that from early childhood we are trained, subtly and not so subtly, to constrain not only our affects but our awareness of those affects so that we will be able to behave in conformity with social expectations. Moreover, Grossman argues, we have been trained so thoroughly that we take our training for nature, and so have strong unconscious view that “such schizophrenia is necessary and normal and that a person who has not succeeded in separating his ‘personal’ life from his ‘professional’ life is in some sense immature.” Grossman goes on to enumerate the devastating consequences of this dynamic for individuals, for societies, and for the planet as a whole but also movingly insists that since this dynamic is not in fact natural but rather devised by human beings we also have the freedom to devise alternatives.

All of this dovetails nicely with Dewey’s ideas on work and play and its associated oppositions. What is particularly striking about this part of Grossman’s argument is that he brings the chickens home to the academic roost. Within the academy, Grossman points out, the phenomenon of social schizophrenia manifests itself as an opposition between reason and analysis on the one hand and affect and appreciation on the other. “The triviality,” Grossman writes,

of most academic research lies in just this point: the kind of analysis given by people who are not personally connected with what they are analyzing – and academics are especially trained to be this way – is necessarily shallow and will at best belong to . . . to the ‘true but useless’ category. . . . Analysis that is separated from inner life is precisely the schizophrenic split that is the root cause of humanity’s collective death wish.

Grossman’s reflections on social schizophrenia and its academic manifestation help to clarify the problems Eva and I had experienced and that Dewey’s reflections on work and play elaborated philosophically. How could I write affirmatively of the joy of loving and thinking that engaging books roused in me without stalling my career? How could I work within the academy in such a way as to make a space for that sort of writing, for myself and others with less institutional power, and still leave other colleagues and students free to do their work the way they saw fit? Why did I have to love privately and think publicly? How in the world did we get to the point where it seemed possible to really do either of these things – loving and thinking – without the other?

We are ensnared in a series of oppositions arising in our minds and related to their enforcement by social institutions and practices: play and work, self and other, subject and object, desire and obligation, affect and intellect. The naturalized hold these oppositions have on our way of experiencing and thinking about the world is the source of much suffering. The suffering arises not from the oppositions themselves but from the fact that we take them to be reflections of the way the world really is, independently of our views of it. We could, for example, see them as mental tools we have devised to accomplish certain purposes and which we should feel entirely free to set down for the accomplishment of other purposes.

Conversely, the erosion of these oppositions and the loosening of their grasp on our experience and thought play a major role in reading to live and in my understanding of what reading can be. And, by extension, in my understanding of the way that reading can be a practice of cultivating joy and freedom in our lives. The question might be simply how to heal. How do we recover from our compulsive, addictive dependence on these oppositions? How do we dissolve or elude the imaginary barrier on either side of which we conceive these dichotomous terms stand? It is perhaps no accident that Grossman’s argument comes in a commentary on Spinoza, because Spinoza provided what is for me perhaps the most compelling and inspiring methods for responding to this problem. Spinoza offered in his Ethics an encompassing and complex view of God, nature, human nature, and how, in particular, humans can move toward greater freedom.

But at the heart of this broad and profound vision is the following simple advice: 1) your emotions and feelings are signs that you are inevitably engaged in the world, for better and for worse; 2) your emotions and feelings provide you with information about the current state of your engagement, particularly whether you are being nourished or harmed by it; 3) attempting to ignore or repress your emotions and feelings does not make them go away, it only deprives you of important information; 4) observing your emotions and feelings and studying their relationship to the actual state of your engagement with the world is already in itself a nourishing, joyful, empowering act and can, moreover, lead you to begin to reconfigure your engagement with the world so as to maximize your nourishing encounters, and positive emotions and feelings, and minimize you harmful encounters, and negative emotions.

The more we become aware of our emotions and feelings, which means first and foremost becoming aware with our bodies (Spinoza’s term for what our bodies feel, for example pleasure or pain, is “affections,” contemporary neuropyschologists like Antonio Damasio in Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorry and the Feeling Brain call this “emotion”) the more we come to understand the complex network of cause and effect which not only impacts our bodies but also leads us to form ideas (whether adequate or inadequate) about what is going on with our bodies. These ideas are what Spinoza calls “affects” and contemporary neuropsychologists call “feelings.” As we develop this understanding and awareness, we begin to realize that while our affects may be responses to external events, i.e. you might really yell at me and my body might really tense or freeze up and sadness might really arise in my mind, our affects are not caused by those events.

Grasping this subtle distinction subtle distinction that our affects are responses to, but not caused by external events, not only rationally and intellectually, but with our whole being, is the lived practice of Spinoza’s Ethics. In so becoming aware of our affects and comprehending them, we increase our freedom in the sense that we increase our ability to behave according to choices grounded in this awareness and comprehension rather than in blind enslavement to our attachment to passing pleasures or aversion to passing pains. We can come to understand these pleasures and pains not as problems to be solved but as information about our dynamic relation with some part of the world. We find that we need not, must not, repress our affects, especially painful affects, in order to free ourselves of their roller-coaster effects. We can learn to experience, be aware of, and understand our affects and use the information they provide to make more joyful choices.

Specifically, for Spinoza, we apply reason to the information they provide to form what he calls “adequate ideas.” The term “adequate” here, for Spinoza, means something like “accurate,” but with an important specification. An “adequate” idea of some thing or event for Spinoza is accurate when it allows us to grasp, at least partially, the chain of cause and effect, which led the appearance of that thing or event. Or, in Spinoza specialist Steven Nadler’s paraphrase:

“an adequate idea of x is an idea that makes possible a full explanation of x. It shows how x is related to its total causal and logical grounds and reveals the absolute necessity of x and everything about x. Inadequate ideas, by contrast, are ‘mutilated and confused.’ . . . Inadequacy is thus a matter of ignorance or a ‘privation of knowledge.’ . . . One knows something about the thing, but not enough to be able to state truly why it is such.”

A similar insight concerning the importance of understanding affect lies at the heart of Buddhist thought and practice. The Buddhist psychotherapist Mark Epstein reaches a comparable point when he writes “the emotions [Spinoza’s affects, Damasio’s feelings] that we take to be so real and are so worried about do not exist in the way we imagine them. They do exist, but we can know them in a way that is different from either expressing or repressing them.” This, according to Epstein, is the shared aim of Buddhist meditation and psychotherapy. Stephen Batchelor likewise observes, for example, of the way in which awareness of the experience of hatred can defuse it: “To stop and pay attention to what is happening in the moment is one way of snapping out of such fixations. It is also a reasonable definition of meditation.”

Stopping and paying attention to what is happening is also a reasonable way of summing up what Spinoza advises we do with our affects in his Ethics. Spinoza’s formal definition of “affects” as “affections [his term for what our bodies feel, recall] of the body by which the body’s power of acting is increased or diminished, aided or restrained, and at the same time ideas of these affections.” For Spinoza an “affection of the body” can be understood as an event that impacts that body. It may be as simple as drinking a glass of water or having a gust of wind blow against your face or as complex as receiving treatment for cancer. With that in mind, Spinoza appears to be saying that an affect is that change in our body’s power to act plus an idea of what it is that has changed. That much just sounds like a slightly more technical-sounding version of what I’ve already described. But what does he mean by “power to act” and, for that matter, by “body” and “idea”?

The phrase “power to act” here is a particularly loaded, complex, and exciting one in Spinoza. For just as the definition of affect depends upon it, so it in turn depends upon Spinoza’s understanding of the relation of particular, finite, or singular things (such Eva or myself) to what he calls, interchangeably, “Substance,” “God” or “Nature.” The power to act is like a lynch-pin, or hinge between Spinoza’s vision of how the universe hangs together and his vision of how our feelings work to nourish or harm our ability to live well in that universe.

For Spinoza, things like you, me, and the mulberry tree out the window are, in the words of Nadler, “a partial and limited expression of one and the same infinite power of God/Nature/substance, manifesting itself in the case of minds through the attribute of Thought and in the case of bodies through the attribute of Extension.” Nadler continues: “Every particular mind, then, is a finite expression of God or Nature’s infinite power through thinking; likewise, every particular body is a finite expression of God or nature’s infinite power in matter and motion. This finite quantum of that infinite power that constitutes each thing is what Spinoza calls conatus, a Latin word that can be variously translated as striving, tendency, or endeavor.” According to Antonio Damasio, we may translate conatus into contemporary terms as “the aggregate of dispositions laid down in brain circuitry that, once engaged by internal or environmental conditions, seeks both survival and well-being.”

The conatus then might be seen as a specific expression of our “power of acting” (or as Spinoza also refers to it “force of existing”). What an exciting concept! It tells us that we all carry within us a power to act that is a portion of Nature’s, or God’s if you prefer, much larger, in fact infinite– power to act.

It’s impossible for me to resist the temptation to say straight away that keeping a human being connected to his or her power to act is of the utmost ethical importance, and conversely, that I can think of no greater tragedy than to come between a human being and his or her power to act. But it’s really even better than this because the conatus constitutes the essence of each particular finite thing: “The striving [conatus] by which each thing strives to persevere in its being is nothing but the actual essence of the thing.” That is, the particular conatus that we have is what makes each of us,and every other singular thing, what it uniquely is and allows us to distinguish it from other things. In other words, our nature is Nature’s and that is infinite.

Our conatus, or power or striving to persevere in our being, “while always ‘on’ and steady,” as Nadler points out, “does not remain unmodified throughout a person’s lifetime, but is constantly subject to change. In particular, the power can enjoy an increase or strengthening or can suffer a decrease of diminution.” What Spinoza calls an “improvement” or “deterioration” in the condition of a particular thing includes the strength or weakness of conatus, this capacity of each thing to preserve itself and resist or elude those outside forces that would tend to destroy it.

And this is where our affects come in. An affect is neither the cause of such a change, nor the new state of that capacity. Affect refers to the transition to the new state of conatus, as well as to the idea (or, we might say mental experience) of that transition. For example, Joy, according to Spinoza is “a man’s passage from a lesser to a greater perfection.” In other words, joy arises when our ability to act in accordance with our essential nature has been increased.

What is completely counterintuitive and even shocking in Spinoza is his definition of strength or power as the capacity of “being affected in a great many ways or capable of affecting external bodies in a great many ways.” We are in our culture used to defining strength as the ability to resist or to manipulate the outside world. But Spinoza here complicates this conventional definition. He makes strength or power into a relational term: a term of measure whose quantity depends entirely on the extent and force of the affective relations in play. The greater our capacity for affect and for affecting the greater the strength or power involved. It means, to put it very directly, that someone sobbing can be showing great strength.

Spinoza divides affects into two types: passions and actions. The most important difference between a passion and an action stems from the way we think about the cause of the affect in question. An affect is a “passion” when we view the cause as external to us. It is an “action” when we view the cause as lying within us, whether or not we “take action” in our everyday sense of the term. For Spinoza, action is freedom. So how do we change our thinking so as to transform passions into action?

We change our thinking by finding what we share with what we are passionate about. This process of finding what Spinoza called “common notions” is what I call reading to live. It is not just passionately enjoying a book as the external cause of a passively activated pleasure (an affect of passion in Spinoza’s terms). It means recognizing myself in the book and in the reading of it as being fundamentally powerful because I am moved and because the book, its author, and the world beyond are all part of, and moved by, the same power that moves me. To understand this is what Spinoza called “forming a clear and distinct idea” of our affect. As he said, “a passion ceases to be a passion as soon as we form a clear and distinct idea of it. . . . The more an affect is known to us, then, the more it is in our power, and the less the mind is acted on by it.”

So it started to seem to me that the issue with Eva, and with me, is that we identified ourselves with our passions. As Batchelor observes of a passion, “By identifying with it (‘I really am pissed off!’), we fuel it.” Especially when the passion is positive we can become attached to it and fuel it further by clinging to our identification with it. Eva and I attributed an external cause to our pleasure, which prevented us from acting fully, in Spinoza’s sense of the word “acting,” and thus, from fully enjoying reading. Following Spinoza’s argument, understanding our pleasure and that its cause lies within us might enhance our enjoyment. Eva was attached to the reliable pleasure that it appeared to her came from passively reading a good book. She was reluctant to risk losing this passion in the attempt to extend the pleasure of reading that book beyond the immediate experience of reading and thereby to transmute her passion into action, her pleasure into joy arising from recognizing that she and the book were joined in ways that increased her ability to exercise her power to act

For Spinoza, every action arises as the result of the transformation of a passion, and that transformation always occurs as the result of the willingness to take the risk of extending our awareness beyond the immediate experience of the passion and its dictates. It feels like the risk we are taking is that of losing our love of reading. When Eva postponed doing her homework, when I procrastinated writing an article or veered between doing whatever I felt like doing or sullenly submitted to what I perceived as externally imposed demands, it was out of the fear that our actions would tarnish the attractiveness of the object of our passions, which we incorrectly believed was the cause of our joy.

I live best when I live joyfully and I live most joyfully when I seek to understand that web of cause and effects that is my existence embedded in a universe, my relations with which I only partly control. When I cultivate awareness of and grasp the productive operations of my own desire, as well as how the lure of my sad passions lead me away from that desire, I am in that instant ”taking action.”

In other words, the act of understanding itself, is active joy for Spinoza. It might not be the euphoric high or rush (“passive joy”) when fate appears to toss an external object across my path that enhances my power to act. But unlike that joy, active joy draws upon my awareness of the impacting event and the ensuing passive joy, and upon my capacity to understand that passive joy, in order to transmute passion into action. I don’t just know that certain things make me feel joy or sadness, but I know, or at least know more about, why and how they do, how they are composed and how I am composed such that they do. And from there, perhaps, I can come to cultivate those relations that increase my power to act and reduce those which decrease it. Which is to say to enhance my freedom and joy. (To be continued)

Read more...