The Course as Work of Art

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

I thought it'd be nice to break-up these predigested, if still very much improvable, chunks of my book manuscript in progress, with something more current. A few days ago I posted a quotation from Lionel Trilling's essay on "The Teaching of Modern Literature." Much of the essay describes Trilling's desire and efforts to present the materials in that course in a way that would shake-up his students. He paraphrases his and his colleagues' stance once they'd decided to give the course:

Very well, if they want the modern, let them have it -- let them have it, as Henry James says, full in the face. We shall give the course, but we shall give it on the highest level, and if they think, as students do, that the modern will naturally meet them in a genial way, let them have their gay and easy time with Yeats and Eliot, with Joyce and Proust and Kafka, with Lawrence and Mann and Gide.

I love the frankly aggressive tone there. Who doesn't want to hit students in the head with a book from time to time? He then goes on to say that the only way to give the course was to do it honestly:to give it without strategies and without conscious caution. It was not honorable, either to the students or to the authors, to conceal or disguise my relation to the literature, my commitment to it, my fear of it, my ambivalence toward it. . . . And so I resolved to give the course with no considerations in mind except my own interests.

Bravo! But what follows as a quick elaboration of his own interests takes my breath away. A concatenation of interests that make dizzying theoretical connections without ponderously spelling them all out and thus, as so many more contemporary works do, somehow managing to appear to do the work for you without having clarified anything at all:And since my own interests lead me to see literary situations as cultural situations, and cultural situations as great elaborate fights about moral issues, and moral issues as having something to do with gratuitously chosen images of personal being, and images of personal being as having something to do with literary style, I felt free to begin with what for me was a first concern, the animus of the author, the objects of his will, the things he wants or wants to have happen.

Nice. Anyway, Trilling goes on to list and gloss some of the books he had students read as a kind of historical back-story, or preparation for the encounter with modern literature (I gather from the essay that the course was a two semester course and he gives us a run down of what he included in the first term). When I hit this point in the essay, I got excited -- making readings lists that I won't ever get all the way through would be one way to describe my approach to the art of studying and teaching literature (I don't want to exaggerate or be falsely modest: I've read a hell of a lot of books in my time; I just can't remember most of them). Trilling's list included parts of Sir James Frazer's The Golden Bough, Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy, Conrad's Heart of Darkness, Mann's Death in Venice, Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morals, and Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents. I like the way that Trilling lays bare the feeling and thought that went into this particular assemblage of texts. It's certainly not the only or even the best list of books I can think of with which to get students ready for a shattering encounter with modern literature -- but I can think of much worse, and Trilling makes a persuasive case, as I'm sure he made a persuasive course. Anyway, my mind then jumped to one of the most memorable course I took as an undergraduate in Comparative Literature at the University of Wisconsin - Madison. I was a fairly recently convert to comp lit, having started college aimed straight for a pre-law Poli Sci degree and then law school in order to become as much like my venerated older brother as possible. So when I took this particular course, I have to say I was very, very excited to have reading lists and to have ways of talking about books, but I really hadn't gotten very far down any literary reading list. Enter Professor David Hayman and his course on Flaubert and Modernism.

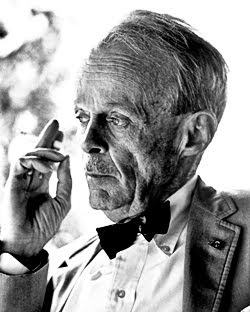

Anyway, my mind then jumped to one of the most memorable course I took as an undergraduate in Comparative Literature at the University of Wisconsin - Madison. I was a fairly recently convert to comp lit, having started college aimed straight for a pre-law Poli Sci degree and then law school in order to become as much like my venerated older brother as possible. So when I took this particular course, I have to say I was very, very excited to have reading lists and to have ways of talking about books, but I really hadn't gotten very far down any literary reading list. Enter Professor David Hayman and his course on Flaubert and Modernism.

I will seem to be contradicting myself when I say I don't remember much of what I learned in that course. I remember Professor Hayman alternately thrilling and annoying me. He was a Joyce and Beckett specialist as I recall and his anecdotes of quaffing pints with Beckett in Paris or Dublin made me feel simultaneously closer and farther away from the great inner circle of literary genius. We had to write weekly page long essays on everything we read and then he would choose a student who got to read his or her essay aloud. Except you didn't know when you read yours whether it was going to be because he liked it or hated it. I read mine aloud once. He liked it. Another boy had to read his twice. Professor Hayman hated them both times. I felt bad for the boy, but also a great sense of relief and superiority.

The thesis of the course, as I recall it, was that you can find the seeds in Flaubert for everything that will subsequently flower, a few decades later, in modernism. I don't think this is a particularly startling thesis. But the way that Professor Hayman got this across to us in the course was, for me at the time and still to this day, fairly marvelous and inspiring. He paired a text of Flaubert with a modernist text. So, for example, we read Flaubert's Sentimental Education and then Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Flaubert's Three Tales with Gertrude Stein's Three Lives, Flaubert's Bouvard and Pecuchet with Beckett's Mercier and Camier. We also read Flaubert's Madame Bovary, The Temptation of St. Anthony, and Salaambo, though I can't remember what we paired them with. And we read Ford Madox Ford's The Good Soldier and Mann's Death in Venice, but I can't remember what Flaubert those were paired with (I recently wrote to Professor Hayman to see if he could refresh my memory).

What do I like about this course? I liked that it provided us with a solid run through the major works of a single author (Flaubert). I liked that it provided us with a substantive, if not comprehensive, slice through a major literary movement (modernism). I liked that it drew on texts from multiple traditions. I liked that it articulated the drive behind its reading list in theoretical terms (centered on the mechanics of modernist narrative techniques). In short, I felt, as I was reading, that I was 1) working hard; 2) learning a great deal; 3) passing some sort of weird but very very important test; and 4) doing all of the above for a reason that, while possibly narrow in scope, made good sense. Most of all, what I liked was the symmetry of the pairings -- especially sweet in this regard was the duo of Three Tales with Three Lives.

Trillings reflections on his course, and my own recollections of Professor Hayman's course remind me of how a great course, a great syllabus, a great reading list, can -- perhaps should -- itself be a work of art.

1 comments:

It sounds great. You should do this course and Lionel Trilling's course. I'd enjoy seeing the course descriptions among the usual suspects.

Post a Comment